Some people cope with chronic illness by relying on others, and I’m no exception. My “other” just happens to be an alter ego I created named Billy Boloby

by Jason Budjinski

The denim-clad rocker types in the front pogoed up and down, drunkenly toasting champagne and splashing it all over the front of the stage. Some got on my white suede shoes, but I didn’t mind. The entire place was electric, and I was too busy feeding off that energy to worry about minor annoyances.

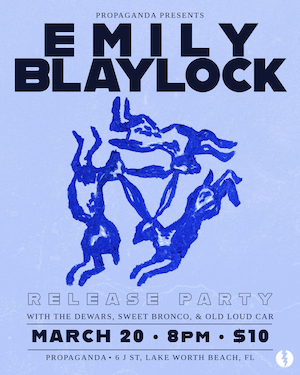

It was Dec. 31, 2003, and my band, Billy Boloby, was headlining the annual New Year’s Eve party at Palm Beach County’s premier alternative nightclub, Respectable Street. As the band’s frontman, I tried to make every performance as engaging as possible — a mix of dancing, pratfalls and general spontaneity.

That’s what Billy Boloby was known for, and Billy Boloby was what I was known for — and known as. People expected to see me fall off the stage and roll around. It was one of Boloby’s more salient characteristics, and something the local press always mentioned when writing about the band.

That was all many years ago.

When the phrase “fall precaution” was most recently written in reference to me, it wasn’t in a newspaper’s A&E section filed under “music.” Rather, it was on a hospital room dry-erase board, under “safety alerts/special needs.” And the name read “Jason Budjinski.” Because at that point, Billy Boloby was gone. Whether he was dead or on life support, I wasn’t sure. I just assumed the worst.

It was March 2013, and I was in the hospital for the second time that month. It’s worlds apart from the stage at Respectable Street, but it’s the only kind of gig I can get without Boloby. He was the attraction. He had a backing band and a local following. I have neither. Rather, my stage is a gurney and my audience is the hospital staff, and instead of careening around stage with a microphone stand, I’m waddling across the room holding an IV pole.

As I stumbled around, constantly getting tangled in IV tubes, all I could think of was how much better life was with Boloby around. He wasn’t just my stage persona; he was my way of coping with chronic illness.

• • •

What began with a routine physical exam snowballed into a never-ending series of tests, procedures and appointments. It started in 1999, when a blood test revealed my liver enzymes were higher than John Belushi on Mount Everest. I was referred to a gastroenterologist to figure out the cause. After three months of tests and procedures, I was diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, or PSC, an autoimmune disease of the bile ducts that eventually leads to liver failure.

I learned two things right away, courtesy of my (now former) gastroenterologist, who seemed to revel in delivering bad news (and whom I referred to as “Doctor Doom and Gloom”). First, there’s no real treatment, the only “cure” being a transplant, and second, people with PSC often have either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. I did some research on those diseases and couldn’t imagine that being the case for me. So, of course, it ended up being the case for me. The doctor discovered I had “subclinical Crohn’s disease,” meaning it was there, but I had no symptoms.

• • •

I was confused. It was just weeks away from my 23rd birthday, and I felt as healthy as ever. On paper, it was a different story. I knew it might not be long before things got hairy, so I vowed to not take any of my remaining time for granted. I knew that surviving this would require an inner strength beyond my normal capabilities. And as a musician, I saw the answer existing onstage — in the form of an alter ego.

Though I had used stage names in previous bands, I’d never assumed a different persona entirely. I’d always wanted to but never had the motivation. Well, I got my motivation, and then some, and I couldn’t wait to get started.

When you’re onstage, you can do things you can’t normally do in “normal” life. It’s understood as artistic license. You set the tone for the room and create the situation; the possibilities are endless. This idea was the guiding principle for the band I would soon form. I already had a general concept for my desired stage persona — equal parts Iggy Pop, James Brown and Pee-wee Herman — I just needed a name. Having grown up watching Pee-wee’s Playhouse, I always loved the name of the ventriloquist dummy, Billy Baloney. So with a little phonetical engineering, Billy Boloby was born, sometime in early 2000.

Boloby didn’t come fully formed right out of the gate; he needed time to develop, finally taking his first onstage steps in May 2002. My first challenge was to convince people I’m really this other person — quite a tall order given his characteristics. Boloby is not burdened by indecision, not worried about doing or saying the wrong thing, or looking foolish. Because of that, he always happened to say and do the right thing. So I had to learn to turn off that part of my brain.

The bigger challenge was performing without a guitar. I never learned how to dance, and because I’m naturally uncoordinated (knock knees, big feet, tweaked ankles), I never was comfortable dancing in front of anyone, let alone an audience. Initially, I tried to work out the kinks and learn a conventional dance routine, but I quickly abandoned that idea. Rather than continue fighting my body’s lack of coordination, I used it to my advantage in developing Boloby’s slack style.

This is where Boloby acted as my “bad health buffer.” As he performed, I took a back seat and let him move with the music, allowing good energy to wash over my body while channeling out all the bad stuff. Yes, I know it sounds silly (and naïve, ridiculous and other such pejoratives), but my thought was this: Because of the autoimmune nature of PSC — in which the immune system attacks the bile ducts as if they were foreign invaders — I figured there had to be a way for my brain to set it straight. I mean, it was just a simple miscommunication, right?

That was my theory, at least, and I was counting on Boloby to be the intermediary between my brain and my bile ducts. Certain songs were written to facilitate this. Boloby’s performance involved a lot of flailing arms and legs, and a continuum of random loose yet jerky movements in accordance with the music. And, notably, occasional bouts of falling down and convulsing. So while everyone thought his antics were intended only for their entertainment, the truth is he was trying to exorcise my illness.

Offstage, the antics continued. Boloby and the other three members of his eponymous band — Gary Harris, Herman Von Uberstein and Marvin Holiday, all alter egos themselves — enjoyed blurring the line between performance and real life. For our first major stunt, we found the perfect outlet for our shenanigans — the infamous supermarket tabloid known as the Weekly World News. The Sept. 3, 2002, edition featured a two-page spread titled “‘Don’t Call Us Freaks!’ Say Deformed Rockers.” The story explained how we met at a summer camp for physically deformed youths, using our love of music to overcome adversity and pursue our dreams. I knew our mission succeeded when I received an email from a WWN reader who thought it was real.

Ultimately, though, our most memorable experiences were live. We tried to have a special theme or skit for each show, and though we couldn’t act, had limited resources and never rehearsed enough, we somehow managed to pull it off most of the time.

Whether it was foreshadowing or mere coincidence, Billy Boloby’s first and only CD, The Revival, was based on a skit we did that involved resuscitating a clinically dead Boloby, who was brought in on a stretcher after supposedly being hit by a car. Now Boloby needs to be resuscitated for real, and it’s up to me to bring him back. I owe him at least that much, considering all he’s done — and continues to do — for me.

Please read the Dramatic Conclusion, Follow Surgery Progression, Donate and/or Show Your Support via his blog:

BILLY BOLOBY’S CYBERLIBRARY

PS: Hit that share and like button for him too!